(This post is adapted from a talk I gave at this year’s College Art Association conference, as part of the “Supporting Creative Legacies in Local Communities: Lessons Learned from the Artists Studio Archives Project” panel session with project Co-PI’s JJ Bauer and Carol Magee and Advisory Board Member Heather Gendron.)

Connie Bostic and collaborator David Dawson with Snakemobile. According to Connie, the kids “belonged to the house next to the church, they just ran out of the house to see the car.”

Digitized from slide

c. 2000s

It was a couple of months after the Asheville, North Carolina artist Connie Bostic had agreed to let me intern with her for a studio archiving project that I learned from a mutual friend what Connie had once shared about (joked about?) her hopes for her legacy. Connie had told her, “When I’m gone, I just want them to take all my stuff out in the yard and burn it in a bonfire.” As unsettling as this was for a nascent archivist to hear at the time, I later came to an understanding of this statement within the context of Connie’s life and work. Indeed, it was through the process of working with Connie’s materials as a student and proto-archivist, seeing them through the lenses of the different roles the “Learning from Artists’ Archives” internship was designed to cultivate, that I came to a fuller understanding of this seemingly tongue-in-cheek attitude towards legacy.

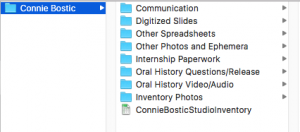

My project with Connie (as touched on in my last post) comprises the digitization of selected slides and ephemera, the creation of an artwork inventory, the establishment of a documentation trail for certain of her works sold or donated to private and public collections, the collection of a limited set of oral histories with and about Connie, and outreach to Asheville’s central library branch to gauge their interest in adding to their collection additional materials pertaining to Connie’s career.

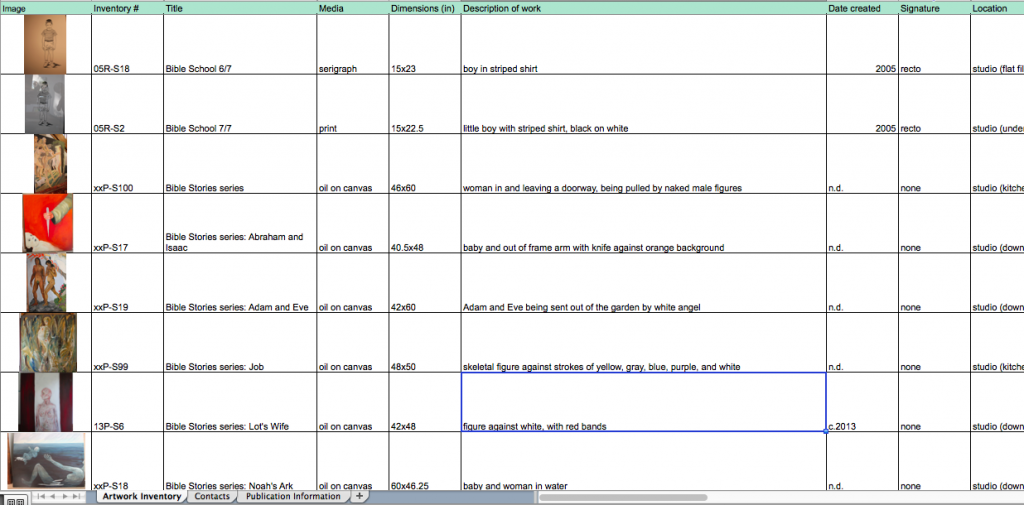

To plan the project, I initially reached out to Connie in February of last year in order to assess her studio needs. Most of the work took place last fall. Initially, we discussed synthesizing and updating her studio inventory, but her old inventory had been physical, and was out of date. I created a new inventory of all the artworks in her studio, as well as those in the collections that I was able to track down from her notes and advice, about 670 paintings, drawings, prints, and mixed media works thus far. While my initial project plan called for a database, the inventory in its current form is in an Excel spreadsheet. Non-archival quality snapshots of most of the works in Connie’s studio are included with each record to make the inventory more legible and usable for her. I digitized selections of Connie’s ephemera, as well as 183 of her slides, numbered to match with inventory entries.

Performing the “archivist” role in this project meant that I needed to develop my working knowledge of what an archivist was, and what sort of archivist I would be in managing this project. In 1970, Howard Zinn’s address to the Society of American Archivists represented a change in the conception of perceived “passive” archiving practices. Instead, he encouraged the development of archival practices geared towards actively seeking records that will help to document the lives of people and communities traditionally underrepresented in archives.[1] I went into this project with an understanding that my choices, even as a student working in a limited way on a collection, are political.

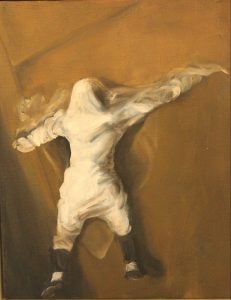

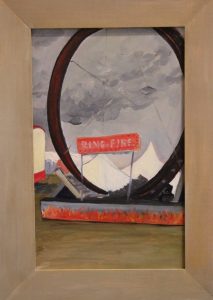

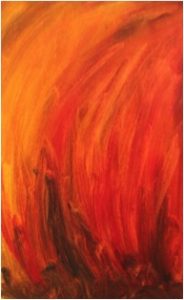

In the case of Connie’s artworks, due to the scale of her collection, I chose to focus on the intellectual rather than physical arrangement of inventory items. Arranging a collection intellectually is like making a map. And of course, “map is not territory.” Early on in the process, answering questions about work titles and dates required sessions with the two of us going through images together to determine approximate dates and titles, if applicable. But in doing so, I also learned about Connie’s practice as an artist–for some works, the titles were vital and the works were timely, tied to specific events and easily dated, such as her Katrina series, her “Day at the Fair” Series, painted on Sept. 11, 2001, or her Mark of the Goddess series, part of her MFA thesis exhibition, the reception of which was tied to a political climate informed by North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms’ attempts in the late 1980s to legislate against so-called “indecent” art.[2] Other of her works could be dated according to her slide library, newspaper clippings, and exhibition materials. At this point, the role of archivist began to shade into that of art historian.

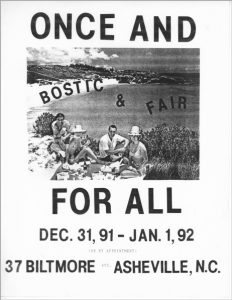

Connie began studying art in earnest in the 1970s, eventually receiving her MFA at Western Carolina University. Later, Connie and Bob Godfrey, the Head of the Art Department there, would run a gallery, The World, together in downtown Asheville, under the umbrella of Western Carolina University. WCU pulled its funding from that gallery a year later in 1987, due to controversy over some of Mapplethorpe’s works being shown in an exhibition there, a small battle in the culture wars. In 1991, Connie opened another art space in the same building, Zone One Contemporary, the first dedicated contemporary art gallery in downtown Asheville. It closed in 2000.

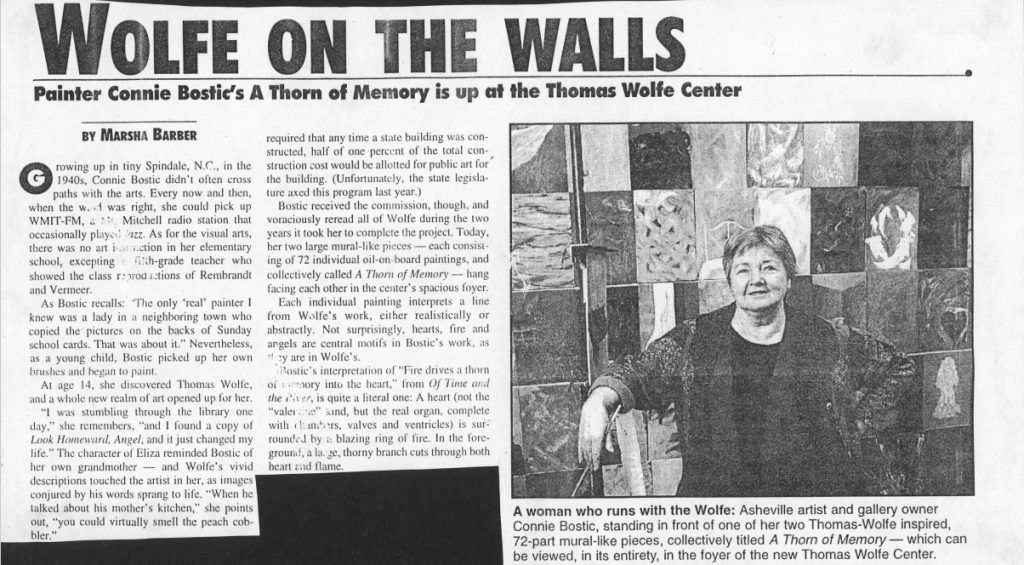

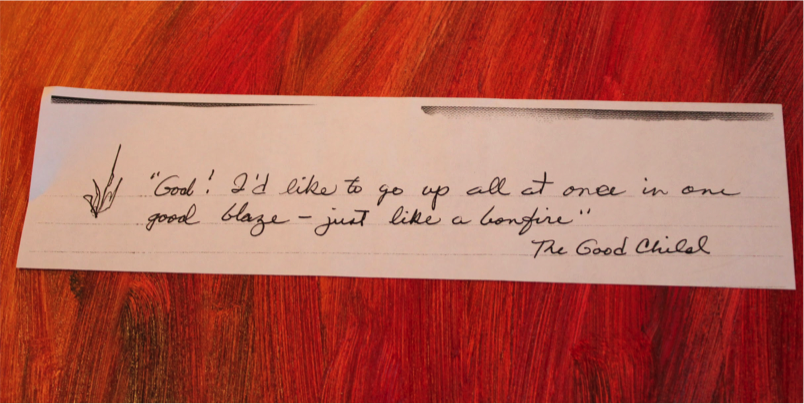

A series of her works, as well as a commissioned mural, focus on the writer Thomas Wolfe, himself a native Ashevillian. As I catalogued these works, I discovered one of her consistent interests, the tension between artistic legacy and physical oblivion. This phrase that she had used among friends to subtly deride her lasting legacy–“burn it in a bonfire”–was drawn from one of her foundational influences, Thomas Wolfe. In citing the fire that she may or may not want to consume her work after her death, she makes veiled, perhaps unconscious, reference to a foundational moment of awakening at the beginning of her life, her discovery of Wolfe’s oeuvre at age 15. At the same time, her remark evinces a rejection of traditional assignations of value to the art object, just as the content of her work undermines comfort with the norms on which those assignations of value rely, especially within her local art scene. Reflecting on this discovery, I realized that my responsibility as an archivist to think about a potential donor’s legacy is nuanced by my training as an art historian, and helps me to understand the complex way that the artist I’m working for conceives of endings and beginnings.

“God! I’d like to go up all at once in one good blaze – just like a bonfire.”

The Good Child’s River

The role of documentarian provides one name for the overlap that exists between archivist and art historian. I conducted four oral histories with and about Connie, to be kept with her collection. Participants include friends, colleagues, and students. In an interview with Connie and Linda Larsen, Connie’s friend, fellow artist, and longtime collaborator, I was particularly interested in documenting the story behind Connie’s controversial MFA thesis exhibition, which was covered in the local press and which I initially learned about while digitizing her clippings and ephemera.

Despite changes in the profession over the last 40 years that have helped us to dispense with the illusion of the ostensibly “neutral” archivist who collects passively, there is still a sense that an archivist should not be too invested in what she chooses to or not to collect and preserve. In general, this is for good reason, in order to avoid conflicts of interest. The valorization of a vague archival neutrality has given way to cultivation of our profession’s diplomatic skills, balancing the interests of stakeholders in a professional and informed manner, while also acknowledging our own interests. All of the roles I’ve discussed are themselves interventions, affecting the archive as it is intellectually and physically organized, the narratives pulled from it, and how it can affect the artist’s career–or perceptions thereof. With my choice of an artist to work with, I was also making a choice about my own understanding of the value of artists’ archives. I chose someone intrinsically local, whose story and work is tied to her community, but who intervenes within larger narratives and movements.

In thinking about the pedagogical effectiveness of this part of the “Learning from Artists’ Archives” program, and about how this internship has better prepared me for my career, I’ve discovered that the experience has generated a recognition that is both practical and political–that my choices are interventions, and therefore I need to be conscious, careful, and accountable for each choice that I make, prepared to base justifications for those choices within an established practical literature. I can’t help but parallel the roles I’ve explored in this project with both the exploration and confrontation of given roles and narratives that Connie deploys in her artwork, as well as with the various roles Connie has performed throughout her life–as artist, gallerist, owner of an Asheville gay bar in the late 80s, dog trainer, art teacher, wife, mother, and grandmother. She wears them lightly, not worrying too much about whether they conflict or fail to hang together in a legible way, confident that they make sense taken singly or together within the context of her life and practice. And so, even as I acknowledge the value in strengthening through specific efforts my performance in the roles I’ve discussed, I strive to do the same.

[1] Zinn, H. (1971). Secrecy, archives, and the public interest. Boston University Journal, 19(3), 37.

[2] Wicker, T. (July 28, 1989.) In the nation: Art and Indecency.” The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1989/07/28/opinion/in-the-nation-art-and-indecency.html