Prior to becoming 2nd year fellows of the Artists’ Archives initiative, our application of knowledge was largely general. We led workshop sessions for groups of artists and presented at library conferences, but rarely did we provide in depth, tailored consultations with individual artists who had particular needs. Starting this year, however, my class of fellows has filled that gap by digging into the second internship required by the initiative: consulting with a North Carolina artist to establish their studio archive.

Tailoring the artists’ archives knowledge to a specific artist’s needs has clarified my understanding of the power of organization on an artist’s practice. It has also brought to the fore what is required of an artist-archivist team before even touching the materials to start the archive. First, we have to get at the underlying psychology behind why and how someone naturally organizes. For my artist, Durham letterpress artist Brian Allen, this meant digging down to (1) how he prioritises, categorises and uses his materials currently, (2) how he intends to use them in the future and (3) how he naturally arranges this materials.

Establishing existing priorities, categories and uses for studio materials is an essential first step for two main reasons, one being the archival principal of ‘original order’ and the other the long term viability of maintaining the archive. Archivists prioritise keeping materials or a collection in original order where it makes sense for the collection’s internal logic and intended audience. The principle of original order becomes particularly vital when an archive will be actively used by the original creator of the collection. To drive the point home, here’s a more mundane example of the impact of original order on making a grouping of items searchable. Have you ever had a family member or friend who decided to ‘help’ you by reorganising your kitchen, closet or desk? Remember how you couldn’t find anything for days (possibly weeks) after? That’s because the priorities and categories they assigned to your materials didn’t align with yours or your patterns of use. In archival terms, they abandoned the original order – the internal logic – of your materials. Like with home organization, the usefulness of an archive only stretches as far as it is navigable from a user standpoint. Understanding current use and workflows regarding studio materials allows archivists to replicate them as appropriate going forward. That way the archive work for and with the artist for which it was constructed.

The appropriateness of maintaining original order is determined, in part, by intended future use of the materials, as well. For Brian, his intended future use of his artistic production as a legacy collection for donation takes a backseat to just having it arranged now so that he’s aware of and can find all that he has and so that he can identify where projects overlap and relate. However, his extensive reference library is another story. Brian expressed an interest in having husband extensive catalogue updated, but not for his current, personal use. Instead, he envisions his library as a community resource that would be just one aspect of opening his studio up to the community as a gallery and learning space. These attitudes towards use of his studio materials and reference collection drive the decisions we made regarding arrangement and how much to alter or maintain his current arrangement, priorities and categories.

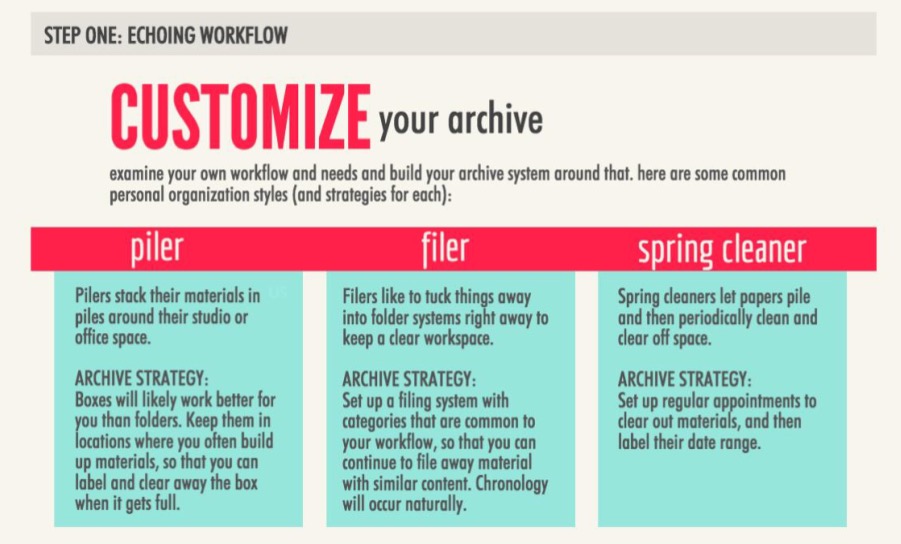

Determining natural organisation practices represents the final step in pre-action preparation for establishing a studio archive. As our physical storage handout outlines, most people fall into three categories: (1) piler, (2) filer and (3) spring cleaner (see image below). Brian, like myself, tends to be a combination of piler and spring cleaner. To make any organisational strategy functional in th long run, the structure needs to follow the path of least resistance. As anyone with failed New Year’s resolutions can attest, maintaining new behaviours that don’t work with natural inclinations or ingrained patterns requires too much effort and too many habit alterations to be sustainable. For Brian’s studio archive, this meant maintaining the categories he’d already assigned his materials, both consciously and unconsciously, in clear plastic boxes that allow him to see both the label and the contents. The boxes are also highly portable and maintained on shelves that also move. His space tends to fluctuate in purpose, so ensuring that his storage accommodated this was essential. Even his oversized materials that require flat file storage are in units with casters and labelled according to their categorised contents. By working with Brian’s natural inclinations and making maintaining the organisation at simple as possible, the hope is that maintenance will feel intuitive and thus not require Brian to employ someone to manage his materials after I finish up my work.