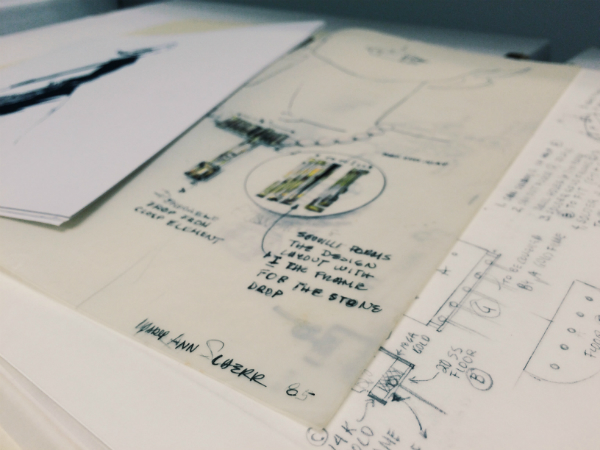

Illustration files from jewelry and fashion design projects;

Mary Ann Scherr papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Cheers from the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, in Washington, DC, where I’m very happily researching and processing artists’ collections. This summer, Colin and I are completing internships at the Learning from Artists’ Archives partner institutions. While I’m at the AAA, Colin is at the Mint Museum in Charlotte, NC (which he’ll be posting about in the next couple of weeks). Working in these institutional contexts enables us to witness and partake in art archives management with experts in the field, gaining a firsthand look at developed and developing standards for dealing with the particular challenges of art archives.

The Archives of American Art

A little background: The Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art (AAA) is the largest, most renowned, and most widely used research center for primary documents of the history of American art. Its holdings include over 20 million art world records, which manifest in the form of letters, diaries, scrapbooks, sketchbooks, business records, interviews and oral histories, manuscripts, project files, teaching files, printed material, photographs, and artwork from artists, scholars, critics, collectors, dealers, galleries, and schools (to name a few of the many possibilities).

My appointment here is with Collections Processing, which is essentially the step that a collection takes after curatorial ingest and before arriving in a researcher’s hands. This involves refoldering and reboxing material into acid-free containers (for long-term preservation); arranging material into hierarchical organizations (maintaining as much as possible the inherent order, narrative, and style of the artist’s original system); documenting the full collection according to AAA’s standards; and writing a finding aid. Our goal is to make information about the collection accessible in a clear and logical way so that scholars, researchers, the public, or whoever has an interest in the artist’s documents can have an idea of what is included and where to find it.

Before we look at an artist’s collection in more detail, I think it’s important for me to proffer the caveat that there is no “normal” artist’s archive. The documents that make up a collection are unique to the methods, materials, processes, and inspirations of each artist. And rightly so: an archive is most useful if it can be a reflection of the artist’s vision and legacy as (s)he sees it. Researchers want to gain an authentic understanding of the artist. And just as each artist is unique, so is each collection. That’s where the value lies.

Thus, this post surveys a specific collection not as a be-all and end-all of archival ideals, but as a singular example of how the materials included can reflect a story and process (or multiple) of the artist.

The Artist

Mary Ann Scherr is a jeweler and designer living in Raleigh, North Carolina. At different points in her career, she has worked in toy design, automotive design, illustration, fashion, and metalwork and held various positions, from Associate Professor of Metals at Kent State University in Ohio to Chair of Product Design at the Parsons School of Design in New York. Scherr gained the most renown for designing what she called “body monitors,” which were works of jewelry that noted and responded to such things as the pulse of the wearer or the oxygen level of the surrounding environment. Prominent patrons include the Duke of Windsor, Liz Claiborne, and Chelsea Clinton. Scherr donated her papers to the Archives of American Art in three installments in 2001, 2005, and 2008.

The Collection

The Mary Ann Scherr papers measure 2.0 linear feet and date from 1941 to 2007. Listed below are the series titles with a select sampling (2 or 3) of the records included in each.[1] For more details, see the Finding Aid to the Mary Ann Scherr Papers.

Biographical Material: the certificate and awards program for Scherr’s receipt of the American Craft Council’s Lifetime Achievement Award; a video-recorded North Carolina Governor’s Award interview for Achievement in the Arts (on DVD); assembled photographs, news clippings, and resumes of the artist, her husband, and each of their children

Correspondence: a letter from a clinical care specialist at the Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Head-Neck Nurses regarding a necklace she designed to cover stomas post-tracheotomy; correspondence with the Smithsonian’s own Renwick Gallery about Scherr participating in a craft discussion at the museum (in 1992)

Writings: an academic paper written by Scherr and George S. Malindzak, Ph.D., of Northeastern Ohio University’s College of Medicine entitled “Personal Monitor Cosmetology: An Aesthetic Approach;” a nomination essay to the National Metalsmiths Hall of Fame

Personal Business Records: notification of the work “Worry Bracelet” entering the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1980); a legal patent for her heartbeat monitor jewelry; pen and graphite sketches in jewelry project files

Printed Material: a pack of craft-themed playing cards from the 2006 Discover Craft NC Exhibition; the exhibition catalog from the Seventh Biennial Beaux Arts Designer Craftsman Exhibition; various clippings from newspapers, magazines, and web articles referencing the artist and her work, including an article on the commercial cookie jar she designed in the 1950s that was sold at Andy Warhol’s personal estate auction in 1988

Photographs: photographs of the artist at work, in her studio, and during her Today Show interview in 1985; photographs of her jewelry on models and standing alone

While the above forms just a small sample of the documents in Scherr’s collection, I want to emphasize that each plays a meaningful role in illustrating the history and legacy of the artist. The family files in Biographical Material, for just one example, are essential not only to inform our understanding of the artist’s personal life (which is significant in and of itself) but also to color our perception of her professional life. Indeed, her husband, Samuel Scherr, was also a designer, working in industrial design and marketing with Samuel Scherr Partners, Fulton + Partners, and as an individual consultant. The two collaborated, exhibited, and even received awards as a unit. These connections are elucidated here, with echos throughout the collection affirming, shaping, and refining this relationship.

The lesson here is to remember that as an artist, you’re curating your own story and legacy with your archives. The things you document will be unique to you as an artist and an individual, and what you choose to include is entirely at your discretion. The nuanced anecdotes and larger narratives that emerged to me as an art historian as I processed the Mary Ann Scherr papers were many, from which I could see a wealth of outgrowths for research and exhibitions: all fruitful, all interesting, and all coloring and continuing an artist’s legacy. The archive could foster an entirely different experience for a family member or a fellow artist. But this is what we’re working to foster when we create, preserve, and share our archives: insight, engagement, and discovery.

[1]Series, i.e. Biographical Material, Correspondence, Writings, etc., are the largest hierarchical groups of filed documents. Generally, collections are divided into series, subseries, folders, and files. We’ll dig into these details a little more in future blog posts.