I’m glad to join Kim in sending salutations from my summer internship at The Mint Museum Archives in Charlotte, NC. I’ll echo her sentiments from the previous post that these internships are a great way to learn more about how arts related archival materials are described, preserved, and made accessible by professionals in the archives and museum field. In this post, I hope to expand on the points that Kim made about processing artists’ materials, but from the quite different perspective of a museum archive.

The Mint Museum

Following Kim’s lead, I also think it would be helpful to offer some background information on The Mint Museum and The Mint Museum Archives. Driven by the tireless efforts of Mary Dwelle and the Charlotte Women’s Club, The Mint Museum was established as North Carolina’s first major art museum in 1936. The museum repurposed the historic Charlotte Mint building, which was designed by noted architect William Strickland 100 years earlier as the first branch of the US Mint.1 The museum has grown over the years, now occupying two locations with strong collections in the areas of fashion, American art, decorative arts, contemporary craft & design, art of the Ancient Americas, and contemporary art.

Initially funded by a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), The Mint Museum Archives was established in 2012 to document the history of the museum and manage the records generated and used by all of the museum’s departments, reflecting the museum’s collections, exhibitions, programming, and community outreach. In addition to materials created by the institution, the archives also collects materials of/from individuals and organizations important to the history of The Mint and the Charlotte arts community. By preserving this record, The Mint Museum Archives not only preserves the past, but serves as a resource for ongoing creativity and innovation in the museum’s activities and the broader community.

Registration Department Exhibition History Collection

One of my big projects thus far has been to construct the finding aid for the Registration Department Exhibition History collection, which serves as a great example of how the archives preserves the history and activities of the museum. Although the records from The Mint’s earliest years are a little bit thin, this collection gathers together the documentation for nearly every exhibition held at the museum from 1936 to 2014. Each file contains the material traces of every aspect of an exhibition: correspondence with artists and other museums planning the show, sketches of where pieces hung in the galleries, copies of exhibition catalogues, biographical materials on artists and details about the artworks, more correspondence after the fact reporting on how the show was received, photographs of works featured in the show, and many other kinds of documents.

This collection not only illustrates how The Mint planned, promoted, and managed exhibitions, but also how these processes have changed over time. Modes of communication shift as telegrams and typewritten letters give way to word processors and e-mail. Changes in stationery and kinds of paper alone tell an entire media history, revealing layers of information beneath the immediate content of the documents. Mint curators go back and forth with organizations, such as the American Federation of Arts, via post to book traveling exhibitions, or reach out to an artist that a friend of a friend has suggested might be interested in exhibiting work. With the earliest materials dating to long before the establishment of accreditation by the American Alliance of Museums, the collection speaks to the development of professionalism in museum practice.

In addition to documenting the history of exhibitions from the perspective of the museum, this collection also captures the lives and activities of artists. Exhibitions are key opportunities for an artist to present herself to a viewing public, who may or may not be familiar with the artist’s work. In conflict or collaboration with the curator, an artist can leverage an exhibition to advance a particular aesthetic position, or craft a certain narrative about themselves and their art. Although this dynamic relationship between museum and artist is manifest throughout much of the collection, there are also quite a few special, unique stories preserved within the file folders.

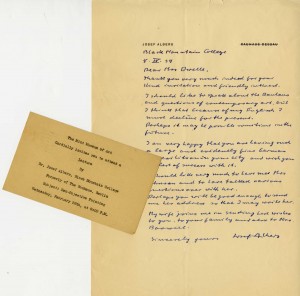

Letter from Josef Albers to Mary Dwelle, Exhibitions, Registration Department Exhibition History Collection, 1935-2014, The Mint Museum Archives, Charlotte, Accession no. 2014.7

In one of the first files that I described for the finding aid, containing documents pertaining to a 1940 exhibition of the work of Josef Albers, I found a handwritten letter from Albers to Mary Dwelle, making arrangements for a lecture to accompany the exhibit. The note is written on Bauhaus letterhead, with “Bauhuas Dessau” crossed out and Black Mountain College written in. The brief correspondence documents Albers’ lecture, but it also obliquely tells the story of his exile from Nazi Germany to North Carolina, attempting to start a new life at Black Mountain, but even still with the shadow of violence lingering.

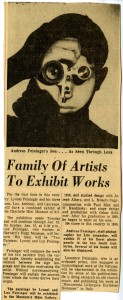

Another story emerges out of the materials from a January 1956 combined exhibition of the work of modernist painter Lyonel Feininger and his three sons Lux (painter), Andreas (photographer), and Laurence (musicologist). The unprecedented exhibition of this especially creative family is fascinating in itself, but the story takes a tragic turn when Lyonel unexpectedly passes away on January 13, 1956, just when the exhibition was getting under way. With the news of Lyonel’s death, the correspondence between The Mint and the Feininger family becomes somber and consolatory—although this tragedy transforms the exhibition into a fitting tribute to the artist, with his legacy embodied in the work of his sons.

Clipping from Feininger Exhibition, Exhibitions, Registration Department Exhibition History Collection, 1935-2014, The Mint Museum Archives, Charlotte, Accession no. 2014.7

While this is an institutional archives, the repository is open and will also be of interest to the general public. The Mint’s history is also interwoven into the cultural history of Charlotte, the Southeast, and, most broadly, the history of art. These examples from the exhibition history collection demonstrate the ways in which a museum plays an integral role in the art world, a liminal space between artist, curator, and viewer. The story of artworks and artists must also include the stories of how objects are shown, received, purchased, stored, deaccessioned, and recycled, all processes that involve the interaction of many different individuals and institutions. The records generated by museums speak to these fertile connections and communications, and so The Mint Museum Archives not only preserves the history of the institution, but of everyone and everything that passes through its walls as well.

1 Unfortunately, I can only scratch the surface of The Mint’s rich history. For more information about The Mint’s early days as a minting facility and its development into a museum, see: The Mint Museum of Art at Charlotte: A Brief History by Henrietta Wilkinson. Also, visit The Mint Museum Archives!