This fall, I had the wonderful opportunity to work with Susan Harbage Page at her Chapel Hill studio as part of my fellowship with the Learning from Artists’ Archives project. In conversation with Susan and (our then PI) Heather Gendron, we decided that the most dire need from an archiving perspective was that Susan’s studio inventory be migrated off of a now-defunct software and upgraded to something that could assimilate to her workflow. However, we found that we wanted (and were able) to take on additional projects as the semester moved along. All three projects outlined below are ambitious undertakings and ongoing efforts to facilitate Susan’s business, legacy, and artistic message while also preparing her career for long-term archival preservation.

Inventory

The first project of the semester, which we had deemed as our highest priority, was the migration of Susan’s old inventory, now out of use, to an updated and more usable interface. Her original inventory was on a system that’s been defunct since 2007. After experimenting and sampling many options for general inventories, business inventories, and art-specific inventories, we finally settled on GYST, a program built “by artists for artists.” GYST is powerful but neither pretty nor intuitive. After much frustration with data finagling, we made peace with the software and peace with the natural imperfection of a working, non-static archival system. Susan’s oeuvre covers several media, including photography, performance, video, and painting, and that work spans several decades, projects, and issues. With the inventory project, our goal was to make sure that information pertaining to these works was searchable, findable, and exportable, so that the business end of gallery and sales management could be expedited and Susan could focus more on her creative process.

Anti-Archive

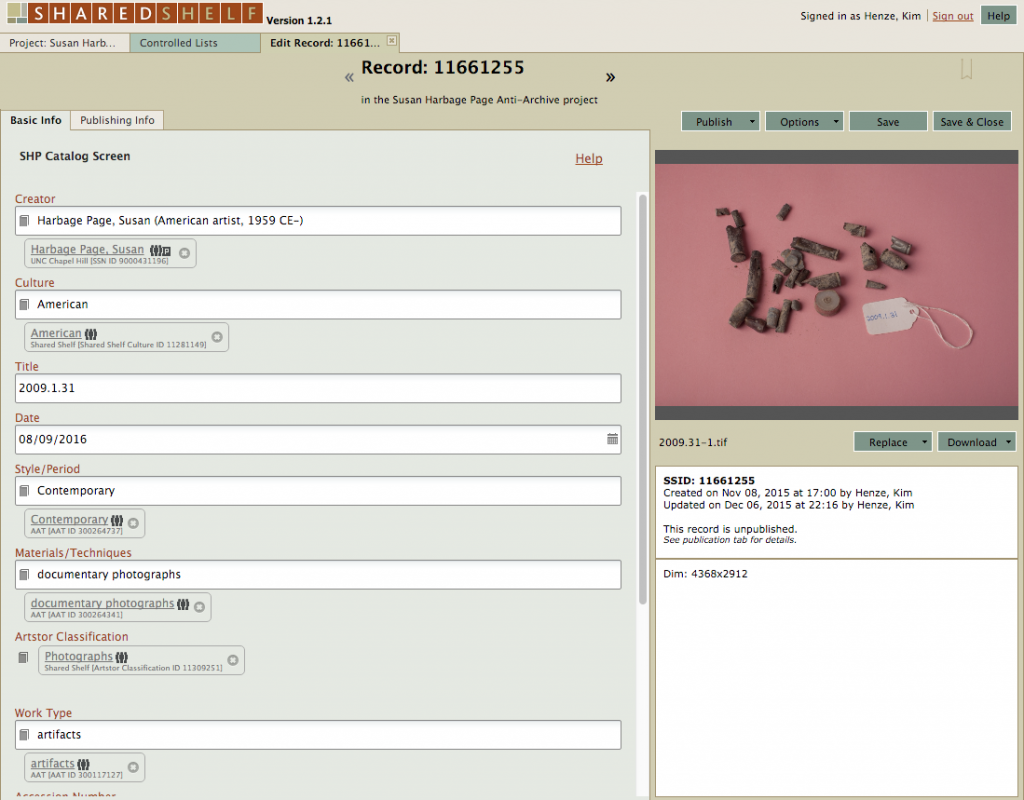

Once we had the inventory project underway, we started on priority two: the Anti-Archive, which is simultaneously art archive, performance piece, photography portfolio, and documentation project. Susan has walked along the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas once a year, every year since 2007, and collects the objects that she finds that have been left behind. These objects, everything from bras and pants to knife blades and ditched IDs, tell the story of struggle as individuals and families laboriously attempt to journey into the United States and, they hope, a better life. Susan collects these objects, gives them accession numbers for her “Anti-Archive,” and photographs them. She also takes in situ photographs of the objects and landscapes along the way and performs artistic and defiant actions, like lying on the border.

The Anti-Archive database project we took up together was an attempt to gather these accessioned images onto a database where the public could see them all at once, download them at large sizes, and have a starting place to learn more and ask questions. We spent some time looking into different options for host platforms, but ultimately ending up going with ARTstor’s Public Collections, which is an academic resource that’s publicly available, can host an unlimited number of very large images, and will include extensive metadata to enable academic and museological study, research, and exploration. There were tradeoffs, however, because originally Susan had hoped that the database could be all the above and also playful, where users could navigate, rearrange randomly, or search by various categories such as color, object type, or year. Unfortunately, we were confined by time, budget, software, and navigability. All in all, though, we felt that SharedShelf is a good archival homebase for the images, providing both scholarly and academic authority, information, and access–and thus a standing monument to Susan’s legacy.

Project Website

Eventually, and perhaps too boldly, we embarked on a third project as well. This was an effort to publish some of the background elements of the U.S.-Mexico Border Project so that users who can see the Anti-Archive objects will have a context and conversation in which to engage. After much experimentation (aesthetics and design being hugely important for an artist’s website), we settled on a minimalist and sophisticated design. We spent time talking about what we wanted out of the site, what kinds of background information and navigability elements are important, and how we would map that out. This third work is still in progress, but the goal is that it will stand as a multimedia space and artistic message for the Border Project. I hope to continue working with Susan as we get more images prepared for publishing and as we have more dialogues and narratives written to publish.

In gathering my thoughts for a conclusion, I’ve reflected again on everything I learned during my semester with Susan. Certainly there are the experiences that make the time worthy of an “academic” three-course credit (time and project management, solo troubleshooting, interpersonal environment, etc.), but it was also a powerful reaffirmation of the importance of this kind of archival work: as an artist, activist, and scholar, Susan had her own lessons learned, stories to tell, and artistic narratives over her tenure with the border project and her entire career as an artist. Working at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art this past summer was hugely illuminating in terms of the findability, usability, and institutionalization of art archives, but in working directly with an artist this last semester, I was given a jarringly intimate look at how much value lies in those kind of narratives and evolutions, and it makes my appreciation for artists’ archives so much stronger.