The last few blog posts have covered Colin’s and my own interactions with collections at our internship sites and have casually employed archival terms like “series” and “hierarchy.” Realizing that such concepts may or may not be cloudy to our readers, we thought it would be a good idea to hash out what we mean when we use them (and also offer some ponderings on what they mean for art archives) a little more concretely.

The collection I’m currently processing comes from North Carolina’s own Robert Ebendorf. In an early research stage, I read a 2014 interview with Ebendorf by Bruce Pepich, the director of the Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin. Here, the artist discusses his creative process and makes the wonderfully succinct and charming comment, “My work has been and is about making order and beauty out of chaos.”[1] In a meta-moment, I was struck by how much this statement reflected my own work in art archives. While the degree of “chaos” of an artist’s papers varies from low to “oh no,” the sentiment of making order and beauty from that ingest is both accurate and poignant. As I’ve said before, our aim is toward accessibility and honest representation, so our organizing schema must be both fairly standardized and adaptable. This is where our buzzword comes in because, most often, archivists manage this through series.

The Society of American Archivists (SAA) defines series as “a group of similar records that are arranged according to a filing system and that are related as the result of being created, received, or used in the same activity; a file group.” That filing system is most often hierarchical, which means that the top-level categories offer the most basic divisions, and every subsequent division is more specific but still honors the divisions and characteristics in its preceding level. A single document is called a file or a record, and exists in a folder (which may be real or virtual) and may stand alone or perhaps with related materials, at the lowest level of a hierarchical arrangement.

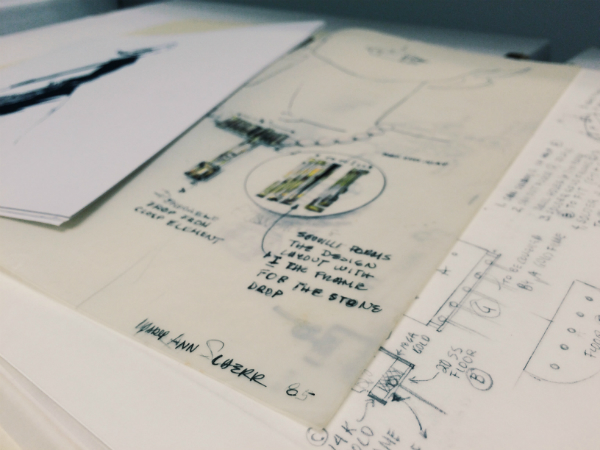

To illustrate with an example, let’s consider the Una Hanbury papers at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art (AAA), for which I processed an addition a few weeks ago. The collection is arranged into seven series: personal papers, business records, project files, subject files, estate, printed material, and photographs. These series titles come from the standards for intellectual arrangement at the AAA, which offers a set of 19 series for describing artists’ and galleries’ papers from which the final series are chosen based on the original structure and content as received from the donor. The standardization here thus comes from the controlled options and the adaptability from the customized selection.

If, within a series, there is still a stark split between different kinds of records, the AAA may use a subseries to further divide the material. In the Una Hanbury papers, the original archivist created subseries within the series of Photographs. Here you’ll notice that photographs of art are separated from photographs of the artist (6.1 Works of Art vs. 6.2 Una Hanbury).

If a collection is large and varied enough, there may be need for sub-subseries, which is exactly what it sounds like — another division for an additional level of specificity — before arriving at individual folder titles. This rarely occurs at the AAA because collections are usually sufficiently navigable after a subseries division. At the lowest level, the folders are titled and numbered for finding and referencing material. The finding aid is written — which is basically an outline of the hierarchy with some summaries and notes of clarification.

So you can see why we so often use hierarchies: they’re navigable and clear and can be physically manifested in folders and boxes because every item exists in one and only one place. The overarching structure of the collection can be clearly imagined, internalized, and navigated by a user. However, this benefit is also a drawback: if an item can only exist in one place, then interdisciplinary material is forced into a single location, and its ties to another concept or entity may be lost, or at least obfuscated. If a single loan book for Exhibition A in Museum A, for example, also has sketches on the verso for Artwork B and a scratched note about Gallery C on a back page, these latter bits of information won’t get represented in hierarchical placement. Likely the loan book will go into a series on Business Records with a folder title of “Exhibition A in Museum A.” Artwork B and Gallery C might get a mention in a scope note, but even so their information is separate from material relevant to B and C elsewhere. An additional drawback of standardized hierarchies is that, even when customized, they almost always demand rearrangement of the original order created by the artist or gallery.

The good news is that, while hierarchies work pretty well for now, there are more options emerging for information organization that could, somewhere down the road, be incorporated into archives systems. I’ll discuss two possibilities below, but the structures and options are sure to change as the library science and knowledge organization communities experiment and re-evaluate user needs and information systems (and as the archives community responds to these developments).

Faceting

Where hierarchy uses a tree structure, faceting uses a matrix. Think of when you’re searching for books on Amazon, which employs both hierarchies and facets. Hierarchy starts from a broad base (books) and then narrows into more precise categories (fiction>historical fiction) as it branches out, but a faceted system employs multiple access points and can be informed from several directions (author, date, genre, rating, topic). You can search these options all at once to focus in on exactly what you’re looking for or discover connections you hadn’t anticipated.

For an art archive, faceting could mean having documents searchable at once by type, form, and content. Searches across correspondents mentioning the same exhibition, for example, could illuminate connections to a reader without her having to look through every letter in the collection.

Linked Data

Rather than a tree or a matrix, linked data is a network of hoppable hyperlinks and connections for discovery. This could manifest as part of the semantic web, where data is linked to enable query of information, construction and discovery of relationships, and even the automated reasoning of those connections through established vocabularies.

For an art archive, this would enable linkages between intra- and inter-institutional collections, as well as to art image databases, library catalogs, museum websites, and artists’ pages. Born-digital material (time-based media art as well as artists’ social media and web presence) can also be integrated into this kind of system.

While neither faceting nor linked data translate well to the physical format (where the one object-one location is binding), if combined with digitization and optical character recognition, we could possibly log all the information and enable intellectual reorganization (on multiple levels) virtually while maintaining in perfect order the creator’s original physical arrangement of materials (which archivists know to have inherent value).

I’m dreaming and projecting a lot with these last bits on faceting and linked data, but I think they are worth keeping in the back of our heads. When we think about trying to make beauty and order out of chaos, as Ebendorf so eloquently mused, we welcome new discoveries and interpretations. Ebendorf said that in gathering and recombining materials, he gives them “new life as part of a work of art.”[2] So it is with our own gathering and arranging of papers that we give documents (and the artist) new life as part of an archive, its own form of a work of art.

____________________________________________________________

[1] Caroline Gore, Lena Vigna, Bruce Pepich, and Robert Ebendorf. Robert W. Ebendorf: The Work in Depth. (Racine, WI: Racine Art Museum), 24.