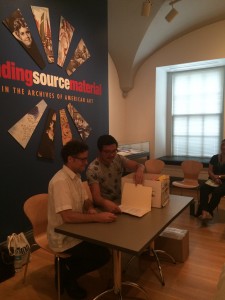

Paul Ramirez Jonas with Josh T. Franco. Photo courtesy of Mary Savig.

“It’s something I wouldn’t give you, or I would double check,” artist Paul Ramirez Jonas said to Archives of American Art (AAA) Curator Josh T. Franco, referring to an item found in a box of studio materials recently donated to the Archives.

Beat.

“Um, it’s already here, Paul,” Franco replied, as the crowd in AAA’s gallery within the Smithsonian American Art Museum laughed.

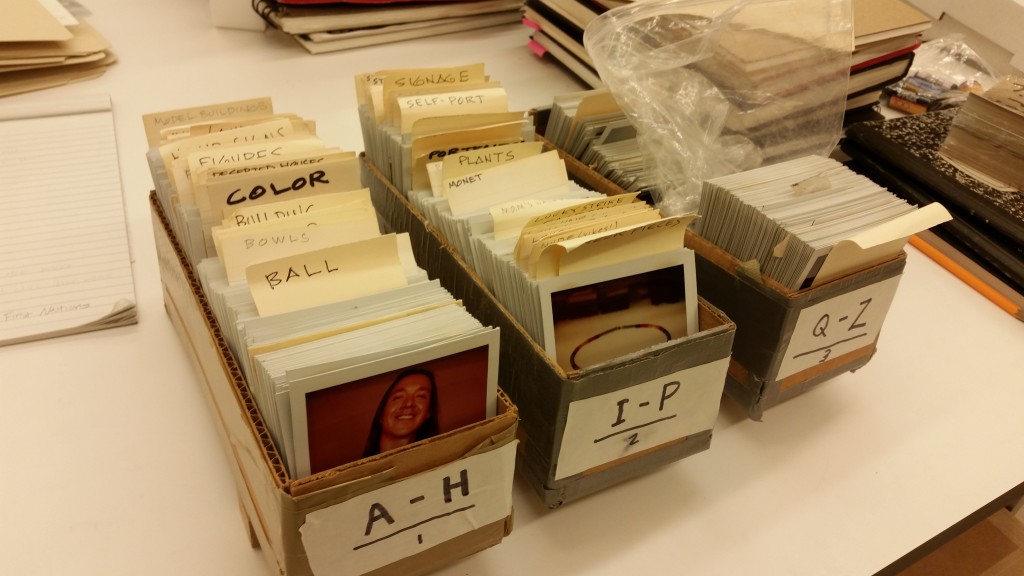

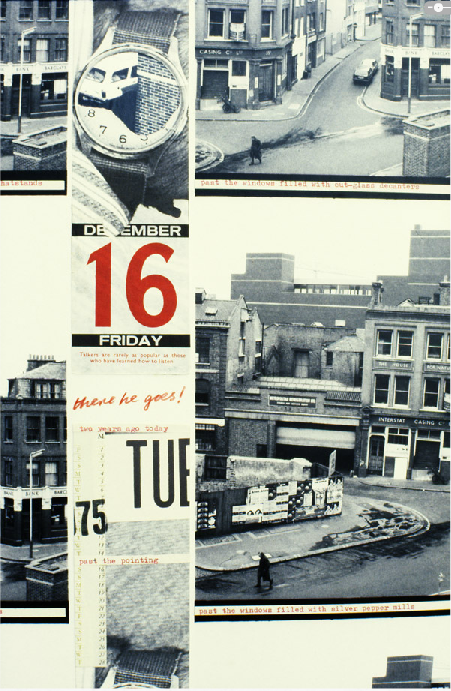

Examining donated archival materials is not something usually performed in front of a crowd, but this event—with the AAA’s current exhibition, “Finding Source Material in the Archives of American Art,” as a backdrop—encapsulated the process of archiving an artist’s materials, while also demonstrating the value of those materials in context. The curator examined the artist’s donated materials, observing organizational structure and how that box fit in with the rest of the artist’s collection. In once instance, Franco came across an empty but labeled folder in the box, joking, “This folder would have to go in another folder as an archival document.” The artist provided contextual details about individual items, recalling memories they evoked, telling the story behind a piece, and in some cases noting that a photo or a slide was the only remaining record of an artwork. Included in Ramirez Jonas’ materials are plans for kinetic sculptures either never completed or no longer functioning. Of those plans, Ramirez Jonas said, “The work can never be as good as the notes,” identifying the division between imagination and reality, intention and the completed work—one of the fulcrums along which archival work, art historical research, and artistic practice pivot.

This summer at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, I’ve been focusing on this pivot point as it appears in the processing of artists’ oral history interviews within the AAA’s Oral History Program. My colleague Kim Henze interned in Collections Processing at the AAA last summer–where she worked with physical materials like diaries, sketchbooks, and correspondence, my focus has been mostly on digital and digitized audio files, as well as their corresponding transcripts.

The program began in 1958, at a time when larger institutions were just beginning to incorporate oral history archiving in a systematic way. The Columbia Center for Oral History had begun just ten years earlier. In the AAA’s Oral History Program, staff contracts art historians, critics, and writers to interview working artists about their lives and careers, documenting not just individual works and voices, but also of specific moments within American art history. Through artists’ immediate description and living memory, the over 2200 oral histories build context and complication for researchers weaving art historical narratives.

The first interviews collected in the program are with artists who had participated in the 1913 Armory Show, widely considered to be the first significant exhibition of modern art in the U.S. Since the 1963 launch of the Oral History Program’s first large-scale collecting project, an oral history of the New Deal art programs, interviews have typically been collected under the auspices of specific initiatives, such as the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and the Decorative Arts in America, which documents prominent craft artists; and Visual Arts and the AIDS Epidemic: An Oral History Project, which examines the impact of the AIDS epidemic on the New York art world of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.[1]

The AAA records about 20-30 interviews a year, depending on collecting initiatives and funding. In 2010, the AAA received a Save America’s Treasures grant to digitize its remaining analog oral histories. In addition to my work with the Oral History Program this summer, part of my job has been to upload these digitized files to the AAA’s Digital Asset Management System.

At the same time, I’ve been researching the history of the program in order to create project pages for the AAA’s launch of its newly redesigned website. I’ve spent the majority of my time, however, moving bottlenecked interviews through the Oral History Program’s lengthy transcript review process.

Untranscribed and unindexed audio is not the most easily navigable format. Because of this, the AAA makes its oral history interviews more accessible to researchers by transcribing them. Alas, this transcription process presents another set of issues for the archivist. First, it’s very time consuming, as well as costly. The AAA transcribes its interviews through third party vendors, but these initial transcriptions must still be checked against the audio upon their return to the AAA, through a process called auditing. Second, the editing of these transcripts can pose questions of institutional policy, ethical practices, and archival theory. During the review and editing of the audited transcripts, artists’ individual preferences regarding their representation within the archive and archival documentation can sometimes collide.

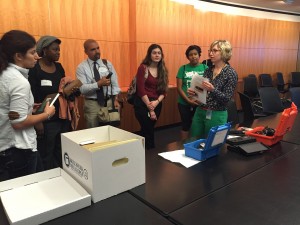

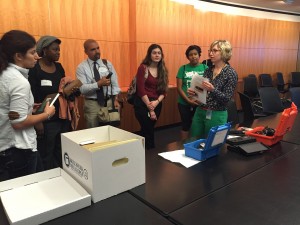

Jennifer Snyder addresses a GWU class on Oral History.

According to the Oral History Program’s currently established workflow, the AAA sends the audited transcript to the interviewer and interviewee (called “narrator”) for the correction of factual errors. The spoken word, however, is very different from the written word—occasionally artists want to make editorial changes or wholesale revisions to the transcription. As mediators within this process, the question that oral history archivists must ask themselves (and the question that has come up in many of my conversations this summer with Oral History Archivist Jennifer Snyder) is: At what point is the transcript an existentially different record than the audio? This is a more important and potentially complex question than it appears to be at first glance.

Transcripts that differ markedly from the audio of oral history interviews can confuse researchers wishing to check the audio against its transcript, as well as institutions seeking audio excerpts of interviews for exhibitions and programs. These texts purport to be that which they are not, i.e. verbatim transcripts of a specific conversation that took place on a specific day. On the other hand, oral history archivists must balance the need for accurate transcripts with the wishes and intentions of the artists recorded. At the AAA, artists sign a “Consent & Gift” form for both the audio and the transcript at the time of the interview—occasionally the material is restricted, but often not. Despite unrestricted donation of this material, however, it is understandable that artists may wish to omit sensitive material, or alternately, material that they deem unimportant to the interview. The very accessibility that makes a transcript more navigable for researchers may be more access than an artist wishes to give. The AAA must balance the legal status of the interview and ease of accessibility for researchers with their ethical obligations to a living interview subject. This is especially true as more and more word-searchable transcripts are added and accessed online.

Within the AAA’s process, narrator and interviewer transcript reviews are received and input into separate electronic documents, those changes are accepted within a transcript, the document is archived physically and electronically, the catalogue record is updated, and the transcript is put online. The AAA currently has about half of its transcribed interviews online, with more going up every day.

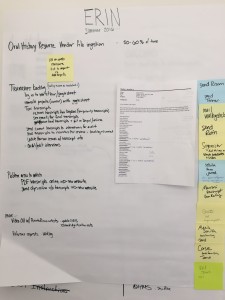

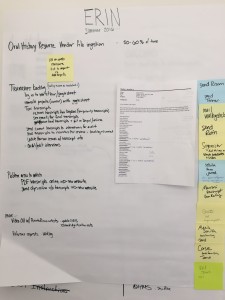

The summer’s tasks.

These complications in making an interview publicly accessible represent a microcosm of the issues artists and archivists face together. I’m ending my summer at the AAA with a stronger inclination that archivists must work with artists to clarify the control they can take in not just organizing their materials, but managing their legacies. This includes informing artists of their rights over their materials and options for restriction, making sure that what they have agreed to donate to a collection is what they actually want to donate, explaining how accessioning and processing work, and supplying scenarios for how their materials will be accessed and used–tasks made even more difficult when an archives is not the primary contact for an artist, such as when an interviewer or contractor without the same knowledge or commitment provides most of the information and facilitates the signing of any restriction forms for an oral history interview. I’m also leaving the AAA with a concrete understanding of the the very real and constant uncertainty that archivists work through in managing the materials of living artists, as well as the limitations that restrictions in time and resources pose.

For all these complications, though, the oral history represents a chance for the artist to respond to their art historical moment, and, perhaps more importantly, to how they may have already been narrativized by critics and historians. For instance, in a 1965 AAA oral history interview by Dorothy Seckler, Robert Rauschenberg responded to the contemporary critical reaction to his Black Paintings (1951-1953), saying:

“…they [critics] couldn’t see black as color or as pigment, but they immediately moved into associations and the associations were always of destroyed newspapers, of burned newspapers. And that began to bother me. Because I think that I’m never sure of what the impulse is psychologically. I don’t mess around with my subconscious. I mean I try to keep wide awake. And if I see in the superficial subconscious relationships that I’m familiar with, clichés of association, I change the picture…Very quickly a painting is turned into a facsimile of itself when one becomes so familiar with it that one recognizes it without looking at it…So if you do work with known quantities, making puns or dealing symbolically with your materials, I think you’re shortening the life of the work even before it’s had a chance to be exposed. I mean, it hasn’t had a life of its own. It’s already leading someone else’s life.”[2]

In this explanation, Rauschenberg militates against the attribution of intention, speaking to critics who might ascribe a subconscious meaning to his work.

In a different vein, Agnes Martin, in her 1989 interview, responded to the common labeling of her work as Minimalist, something she disagreed with on both practical and theoretical grounds, but chose not to protest. Of an early show in New York with nine other artists, she said:

“They were all Minimalists, and they asked me to show with them. But that was before the word was invented. And I liked all their work, so I showed with them. And then when they started calling them Minimalists they called me a Minimalist, too…Well, I let it go, but—I didn’t protest, but I consider myself an Abstract Expressionist.”[3]

And just this summer, in the course of the review process for the interview of Chicago painter Vera Klement, Klement objected to her interviewer’s characterization of her work as “abstract”, and requested a postscript be appended, clarifying:

“I spend much effort making the images…recognizable and believable as three-dimensional objects…They are icons from a common source, images that are in the collective consciousness, described by Aby Warburg as Urformen in the early 20th century. The unusual presentation of these objects doesn’t render my paintings ‘abstract’…”[4]

These clarifying voices are vital precisely because they can both complicate and sharpen overarching narratives, easy definitions, and overly obscure labels. This is the value of oral history—that people, when questioned, don’t always say what they are expected to say.

During the gallery event I described at the beginning of this post, the artist, the curator, the public, and the archival box were in one room. What a luxury! It was a rare, if limited chance to clarify issues that are often so muddled in archival work. What does a record represent, and what is its physical and meaningful relationship to other items within a specific location or collection? How does an artist represent her/himself, and how might s/he want to be represented? What should an archivist, a curator, or an art historian make of the daylight between the “does” and the “want”?

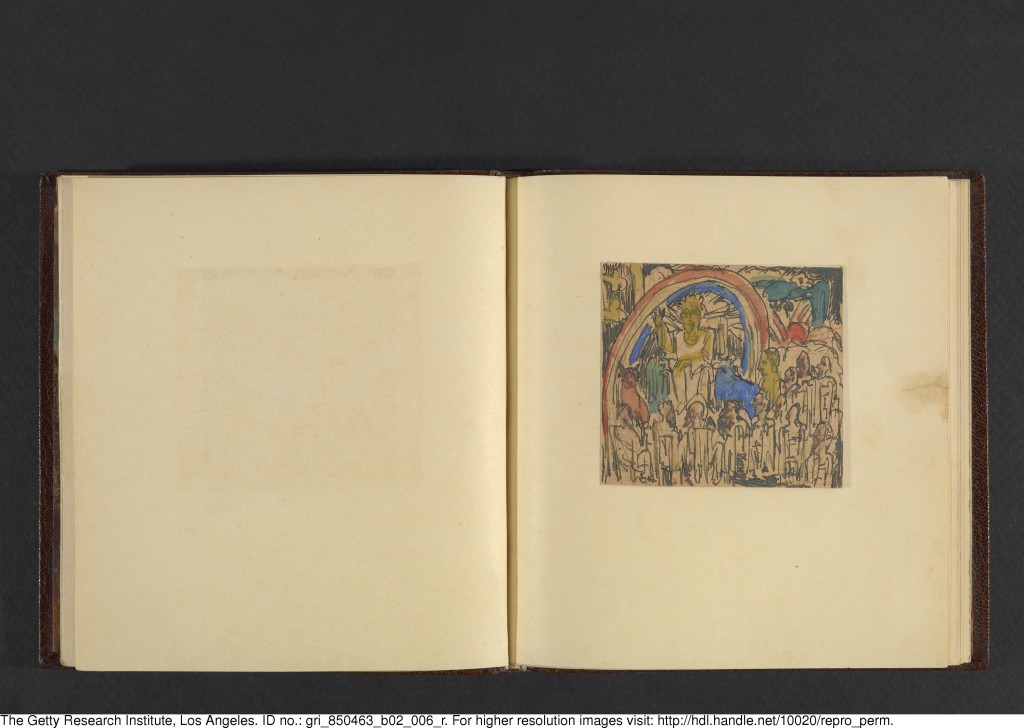

A glimpse at AAA collections storage.

At the end of the session, Ramirez-Jonas, whose work often explores the relationships between the artist, artwork, and audience, responded with a metaphor to a question about when and why he began organizing his materials.[5] He said that he started early in his career and advises young artists to start now, because “Archiving is like brushing your teeth, you need to do a little every day, so you don’t get gum disease.” And what’s the archival equivalent of gum disease? Not just disorganization, but a loss of control over your own materials. Referring to studio archiving practices, Ramirez Jonas noted, “We don’t train artists to do this.” It’s true, and one of the cultural preservation issues that my colleagues and I are hoping to address in the “Learning from Artists Archives” Program.

Notes:

[1] In an interesting piece of serendipitous archival trivia, Kim Henze, during her internship at the AAA in summer 2015, catalogued the first interview that would eventually start the oral history program, a 1956 interview with Atta Medora McMullin, wife of Alson Skinner Clark, donated as part of Clark’s papers. The interview is only existent now in a transcript. Seven years later, in 1963, the AAA began actively collecting oral histories.

[2] Rauschenberg, Robert. Interview with Dorothy Seckler. December 21, 1965. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-robert-rauschenberg-12870.

[3] Martin, Agnes. Interview with Suzan Campbell. May 15, 1989. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-agnes-martin-13296.

[4] Klement, Vera. Interview with Lanny Silverman. June 12-14, 2015. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[5] Ramirez Jonas, Paul. “Statement.” Accessed on July 30, 2016. http://www.paulramirezjonas.com/selected/refImages/CV/statement.pdf