With the “Learning from Artists’ Archives” project, students, artists, museum, library, and arts information professionals, and art historians are collaborating on ways for North Carolina artists to preserve their materials, with an end goal of strengthening the historical record of NC artists’ materials. In this project, we’re all stakeholders. In the past few posts, my colleagues Colin, Kim, and Fannie have focused, respectively, on how artists might preserve their own materials in genres which have traditionally resisted preservation, on one artist’s design and planning process for her current archiving project, and on one librarian’s efforts to create archival files documenting the careers of artists in her community. In all of these projects, the roles of the artists and arts information professionals involved are explicit. The impact of these archiving projects on the final set of stakeholders I listed above, art historians (and with them, other scholars, students, and arts enthusiasts), is less immediately tangible. As we gear up the planning for our next Artist Studio Archives workshop at The Mint Museum in Charlotte this October, I wanted to explore the ways in which people are learning through artists’ archival materials presented online. In order to broach the scholarly impact that efforts to archive artists’ materials makes and has the potential to make, I’ve been looking at the use of artists’ archival materials in the larger context of Digital Art History research.

Digital Art History, like its parent field, Digital Humanities, means different things to different people, precisely because it can encompass widely divergent sets of data and ways of exploring that data. In one of the texts working towards defining Digital Art History as a method, “Is There a ‘Digital’ Art History?”, Joanna Drucker distinguishes between a “digitized” art history as one built on the use of online resources (repositories and image collections) and a “digital” art history which uses analytic techniques enabled by digital technology in order to think (or rethink, as the case may be) art historically using digital processes.[1] This might entail collaborative image and artifact viewing and annotating; map, timeline, and network building; or other tools and processes incorporating digital materials. Though useful as a conceptual framework for classifying various modes of digital humanities research, not all digital art history tools fit neatly within this dichotomy. Given that this field is still emergent, how are art historians, archivists, and librarians using digital tools to present and study artists’ archival materials? What might these new uses and ways of conducting art historical research mean for the choices artists make about archiving their materials?

Both Colin and Kim have given examples of how artists use their digital archives as a means of either structuring the narrative about their materials, or working against the imposition of any single explanatory narrative on their work. Susan Harbage Page’s envisioned “Anti-Archive” of her U.S. Mexico-border project is characterized as an art archive, performance piece, photography portfolio, and documentation project” (despite the ultimate time and budget-based restrictions in realizing the originally conceived open navigability and playfulness in its online manifestation). As described by Colin, John Latham’s archive pushes visitors to mediate their experiences with his materials by choosing among portals leading to different arrangements of the information, provoking reflection on how information arrangement might determine historical narrative creation. These examples demonstrate how artists are using digital tools to present their archival materials, but what are other ways in which art historians and information professionals, perhaps in collaboration with the artists themselves, are using artists’ archival materials online to generate further study?

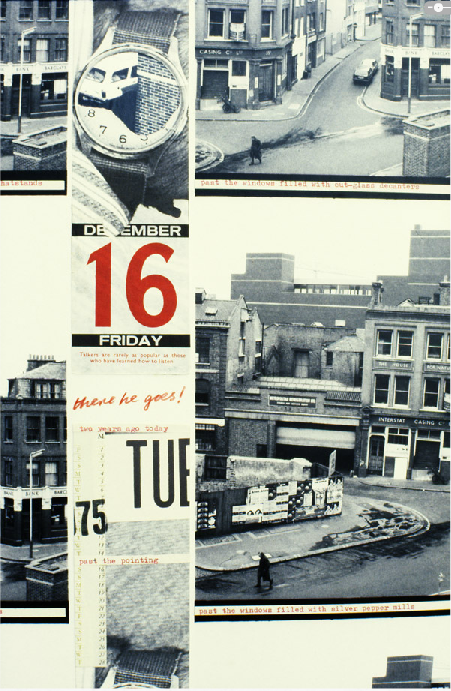

The Diary Re-invented, a 2007 project with artist Ian Breakwell and Jane Gibb and Felicity Sparrow at the University of the Arts, London, presents a visual diary of Breakwell’s images and texts from the 1960s-2000s, browsable via a timeline. Breakwell’s full oeuvre includes visual texts, drawings, photo-collage, events, theatre performances, film, film performances and expanded-cinema events, installations, environments, video, audio works, slide-tape sequences, digital imaging, and readings of prose texts. Breakwell explains that his diaries “record the side events of daily life: by turns mundane, curious, bleak, erotic, tender, vicious, cunning, stupid, ambiguous, absurd, as observed by a personal witness.” He identifies his own themes as the “investigation of the relationship between word and image…the concept of personal time, and the surreality of mundane ‘reality’.” The use of a digital timeline to organize these archival works encourages the user to explore the emergence of these and other themes over time. Some entries are annotated, while the users must explore others without a guide. The website, part of Breakwell’s Arts and Humanities Research Council fellowship project at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, is not an online artist’s archive per se, but instead takes a form of work or works that would traditionally be considered a part of an artist’s archival holdings, the diary, and reconceives it in digital form.

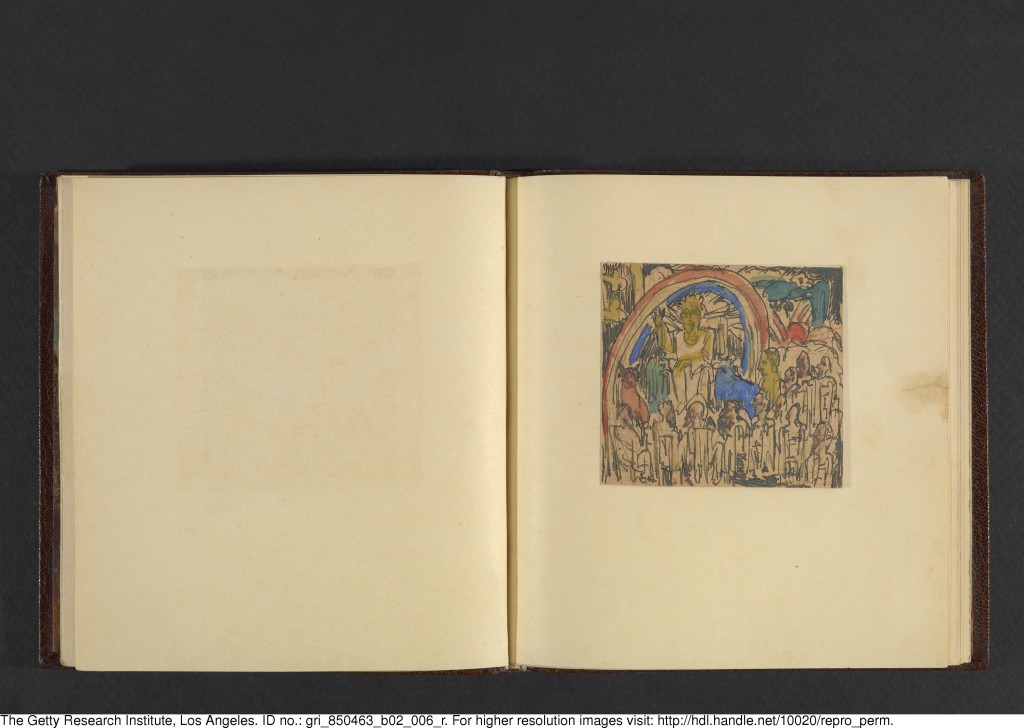

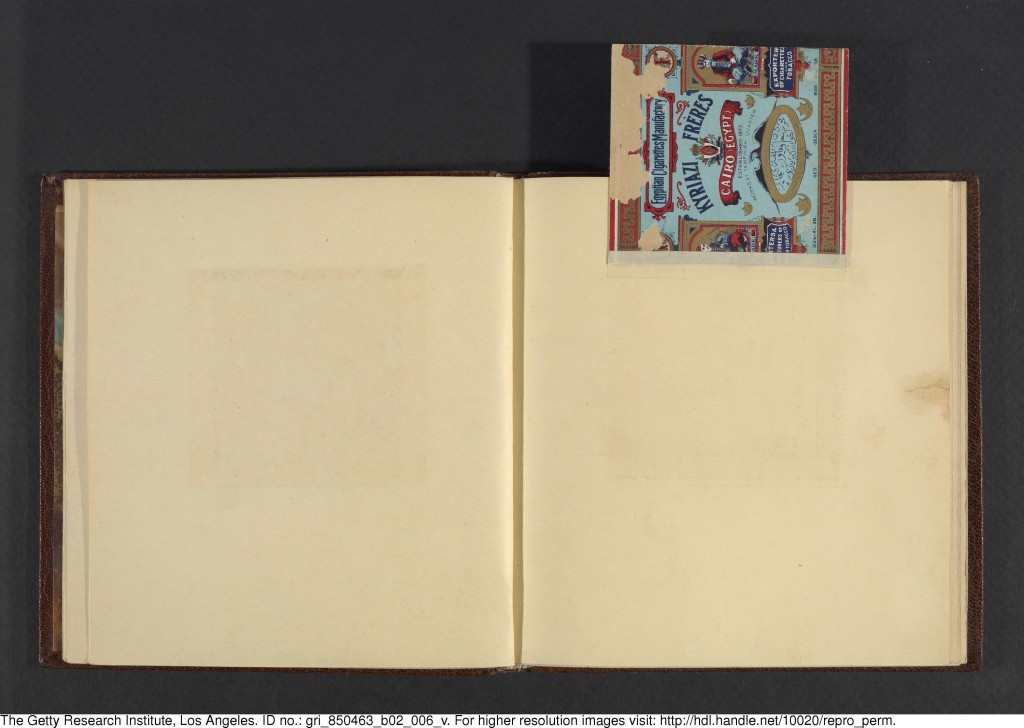

A digital project of a different scale, Digital Kirchner, a Getty Research Institute initiative, centers on a 1917 series of illustrations of the apocalypse created on the back of cigarette boxes by German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938). The project involved digitizing the drawings, which were kept in a sketch album preserved in the Research Institute’s special collections. Team members Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Anja Foerschner wrote a scholarly essay about the works, examining the historical and biographical context in which they were created and comparing them to Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse woodcut series.[2] Though this project may appear at first to be a “digitized” rather than “digital” art history project, to use Drucker’s dichotomy, the digitized album was used to develop a beta version of the Getty’s online collaborative platform, the Getty Scholar’s Workspace, released late last year. The Workspace provides a research environment and set of tools (bibliography builder; image comparison, editing, and annotation tools; text editing and annotation tool; correspondence forum; archival material/manuscript presentation tool; and timeline builder) to facilitate communication for research teams examining digital surrogates of artworks and primary source materials. Though this particular project resulted in a research paper, other Workspace collaborations might result in exhibitions, conferences, or other types of publications. In this instance, one artist’s archival materials were used to help build a new way of conducting research within the still-nascent discipline of Digital Art History.

The gulf in style and institutional scope between the Breakwell and Kirchner projects demonstrates the openness of the field of possibilities for Digital Art History projects using artists archives. Though many current digital art history projects draw widely on different artists’ archival materials held by a number of repositories, the number of digital humanities projects, other than databases and digitization projects, that focus within a single artist’s collection is still quite small. Because digital humanities methods allow scholars to organize and present larger quantities of data than traditional methods, the temptation has been to examine larger quantities of materials than a single artist’s output. The projects listed above demonstrate the value of focusing the digital humanities lens on a single artist or set of works. While the work we’re doing in the “Learning from Artist’s Archives” program will help to build a larger and richer set of NC artists’ materials for future art historians and students to draw upon, I hope that strengthening artists’ agency in actively planning, building, and maintaining their own archives will help to shape the future of digital art history and facilitate scholars’ closer examination of the contexts surrounding a single work, set or works, or legacy.

NOTES

[1] Joanna Drucker (2013). Is There a “Digital” Art History? Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation, 29:1-2, 5-13, DOI: 10.1080/01973762.2013.761106

[2] T. W.Gaehtgens & A. Foerschner (2014). Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Drawings of the Apocalypse. Getty Research Journal, (6), 83–102. http://doi.org/10.1086/675792