In early August, I met with the artist Cornelio Campos at a coffee shop on 9th Street in Durham, North Carolina. I had a collaborative project to propose to him: building an archival collection of his personal papers documenting his career as an artist, and in turn donating the materials to the North Carolina Collection at the Durham County Library for long-term preservation and use by the community. Cornelio was immediately intrigued by the idea, but had one big question—what exactly did I mean by “archive”? Like many people, Cornelio had a vague notion that an archive is a corpus of old letters, photos, and newspaper clippings, but did not know much about the specific work that goes into arranging, preserving, and providing access to and archival collection. Throughout the meeting, Cornelio described all of the stuff that he had accumulated over the years, and expressed a deep understanding of how this body of materials spoke to his development as an artist, but was unclear as to how we would go about turning this stuff into an archive.

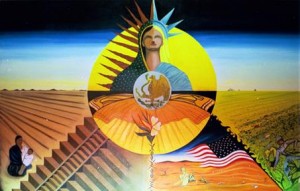

Cornelio Campos installs “American Dreams/Sueños Americanos” exhibition at the Global Fed Ex Center, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

For the rest of the meeting, we talked in more detail about what this project would entail, and for the duration of the project, we have kept a larger conversation going about what an archive is and what Cornelio’s personal archival collection means to him. I explained the steps that we would go through to build his archives: we would sift through all of the papers, photos, and other materials he had saved, appraising them for archival value; using archival storage materials from the North Carolina Collection, we would arrange everything into folders and boxes in an order that made sense to him; we would then describe the collection, creating documents to help future users access specific materials; finally, we would transfer his personal archival collection to the Durham County Library for long-term preservation.

As the project has progressed, we have had extended discussions of both particular archival processes, as well as broader, conceptual questions about archives. We have talked about how to create a finding aid, and the function that this document serves in helping users to understand of the scope of the collection and to access particular folders. These discussions have then led directly into doing: we talked about finding aids, but then Cornelio and I worked together to write the finding aid for his own collection line by line. Cornelio’s active participation in all stages of the process has not only given him agency in the construction of his archival collection and therefore control over the shaping of his legacy, but has also allowed him to develop a rich understanding of archives, serving to address the question Cornelio posed to me at our initial meeting. As archival materials are tightly guarded by archivists and attentively maintained within closed stacks, it is no wonder that archives are a mystery to those without any insight into what goes on behind the scenes. However, this project has equipped Cornelio with new knowledge and skills, helping him to think archivally about his personal materials.

In addition to topics like finding aids and preservation-friendly photo sleeves, Cornelio and I have also had the opportunity to discuss bigger archival issues. On several occasions, Cornelio has expressed to me his excitement about this project and the potential value that his materials will have when they are transferred to the Durham County Library. Many students, peers, and friends of Cornelio have asked him throughout the years if there was any way they could look at fliers and photographs from past exhibitions and any other archival materials he might have. While he has not been able to provide access to these materials in the past, he will now have a single, publicly accessible place to direct individuals interested in researching his career as an artist. Before this project, Cornelio’s personal papers were scattered around his house, making it difficult for even Cornelio to locate a photograph from a particular show or a piece of correspondence with a gallery. Now, these accumulated documents come together to tell a story of Cornelio’s development as an artist—a story that Cornelio himself has had a hand in shaping.

Maintaining this personal archival collection at the Durham County Library will provide many immediate benefits to Cornelio and others interested in his work, but we both hope that this project becomes part of a larger effort to document the Durham arts scene. The North Carolina Collection is committed to preserving archival materials that speak to the political, social, and cultural history of Durham, but before establishing this relationship with Cornelio, the NCC had very few collections from local visual artists. Perhaps many local artists are like Cornelio, accumulating materials over the course of their careers, sensing that these items have lasting value, but not wholly realizing that institutions like the NCC are resources for the community to preserve and share these very kinds of personal archival materials.

With this internship, I was able to start a conversation between the archivists at the NCC and Cornelio, where both sides were able to see the long-term value of Cornelio’s personal materials. As a result of this relationship, hopefully other artists in Durham will take notice and feel that their own personal archival collections might belong at the Durham County Library as well. Cornelio has thrived as an artist in large part because of a supportive community of other artists, galleries, and arts advocates. With the addition of archival materials from more of these individuals, the NCC could truly document not only Cornelio’s career, but the broader community of Durham artists as well. The relationship that Cornelio established with the archivists at the Durham County Library could serve as a model for other artists to follow, adding to the richness of the documentary heritage of the Durham arts scene for present and future users.

As Kelsey Moen mentioned in the last blog regarding the Archiving for Artists workshop, many artists remarked that thinking and talking about the archival value of their personal materials with archives professionals positively impacted their self-image. Like Cornelio, many of these artists participated largely in local arts scenes, and without the reputation of a nationally or internationally exhibiting artist, did not consider that an institution would prize their personal archival collections as valuable cultural heritage materials. As my project with Cornelio illustrates, establishing lasting and mutually beneficial relationships between an artist and a local archival institution can be as easy as starting a conversation, although both parties need to be ready to listen and to gain an understanding of the expectations and needs of the other side. I believe that my project with Cornelio has been a success because both the NCC and myself have treated Cornelio not just as a donor of significant, archival materials, but as a partner in all stages of the process.