Over the past couple months, I have been conducting research into how new media and installation artists think about the preservation of their artworks, including those that are in the process of creation, as well as those works that remain in their custody. The preservation of new media artworks is a fascinating and complex research area, and, as with many topics in digital preservation research, this is a quickly moving target. Namely, this is because new media artworks break the mold for art conservation practices for static, physical artworks like paintings or sculptures, meaning that conservators, archivists, and other art information professionals have had to start from scratch to develop innovative preservation and conservation strategies. A number of difficulties that new media artworks pose include: 1) rapidly obsolete hardware and software, rendering portions or all of the artwork inaccessible after just a few years; 2) interactivity and a lack of fixity, making it difficult to separate the ‘work’ from its reception, or to even consistently define what the ‘work’ is; 3) complex combination of analog and digital components, many of which may be site-specific or configured for a certain exhibition space.1

Over the past 15-plus years, leading arts institutions have begun to develop flexible solutions to address some of these challenges, including documentation models attuned to the complexities of new media art,2 tools to help artists and conservators negotiate variable preservation strategies,3 and emulation platforms to re-present work dependent on defunct hardware or software.4 While these developments point towards a potentially viable approach for institutions to preserve new media artworks in their collections, researchers have yet to thoroughly address what happens to these kinds of artworks that never make it into a museum collection. Although contemporary artists increasingly incorporate new media technologies into their creative practices, still relatively few institutions collect or exhibit new media artworks.

As a result, these artworks largely remain in the personal archives of the artist. Without the resources of an institution, how do artists store, maintain, and preserve these artworks? What factors might artists consider in deciding whether or not to commit time and money towards preserving a work? These are some of the questions that have been driving this research project. Currently, I am wrapping up the data collection phase of the research (which has included interviews and studio visits with eight artists in total, as well as collecting artist statements, photos, and other information about artworks off of the artists’ websites), and starting to move into data analysis and writing up my findings. So, this is a perfect time for me to reflect on the research so far and posit some initial thoughts. In the rest of the post, I’ll offer brief sketches of three artists’ preservation practices, and then close by suggesting some broader implications.

Lile Stephens builds sculptures and installations by re-purposing parts from various electronics, which he describes as his “raw materials.” For Stephens, his artistic process is a form of inquiry into issues in science, engineering, and computing, with his artworks more as byproducts of these investigations. For a recent exhibition, Stephens explored flight technology, constructing a sculpture that linked a model plane built out of electronics to a Google Earth flight simulator.

Works like these are difficult for Stephens to maintain, but a primary reason is that they take up valuable space and there is often little incentive to keep these kinds of sculptures intact once they’ve been exhibited several times. Stephens expressed that it is nearly impossible to sell such complex sculptures, nor would he feel comfortable selling this work to a collector or institution without the resources to preserve it over time. After Stephens has thoroughly explored a particular area of investigation, he also becomes less and less interested in maintaining older work for potential re-exhibition, and would much rather devote time and energy to creating new work that explores new intellectual terrain. Stephens documents all of his work, putting photos and videos on his personal website as well as on countless hard drives, and also often retains schematics, plans, and other archival materials related to previous works, but in many cases the work itself ceases to exist as a physical object. True to his own aesthetics, Stephens will often strip past works for parts, and use these for new projects.

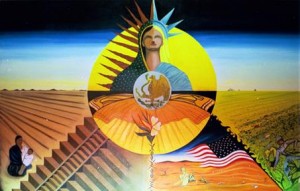

Stacey Kirby is an installation and performance artist (and was our invaluable point person at the NCMA for our first artist archives workshop!). Kirby uses a variety of analog and digital techniques to create installations that engage participants in conversations about where the personal and the political meet. We discussed in great detail how she is currently maintaining a piece called The Power of the Ballot, for which Kirby has created her own voting precinct out of 100 carefully designed cardboard Banker’s boxes.

While the cardboard makeup of the installation presents one set of physical preservation challenges, a broader concern is how to preserve the performative and interactive aspects of the work. For the full version of the piece, two performers staff the booth: one inside the booth taking ballots and one outside the booth interacting with participants. Ideally, Kirby herself performs the part of the voting officer, discussing voting issues with viewers of the work, but this has not always been possible in the work’s exhibition history, nor would it be possible if the work were to be collected. Kirby has devised strategies for this, including thoroughly documenting past performances, which could be used to inform future installations of the work. Perhaps the most important strategy though, is Kirby’s own flexible attitude towards the work. She doesn’t strictly define what The Power of the Ballot is, but makes room for variability. As Kirby describes, “With my work, I’m showing it over, and over, and over again. It’s typical for hanging a painting on a wall and showing it over again, but this has a new life every time. It’s the same piece, but it keeps growing in a way and evolving in a way that is unique to my work.” Over the course of installations at CAM in Raleigh, the Nasher in Durham, and SECCA in Winston-Salem, Kirby has allowed the piece to grow and has learned valuable lessons about what particular aspects are essential to the work and what aspects can be adapted given the constraints of a particular space. This variability will enable the overall work to be preserved for the long term, even if particular components (like the digital files used to design and print the ballots) need to be replaced or reworked.

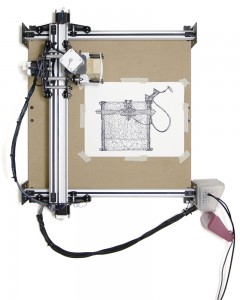

Daniel Smith is a sculptor working across digital and analog mediums, creating forms that can be printed out but can also be viewed virtually through venues like Smith’s own VR exhibition space Paper-Thin. As expressed by nearly all of the artists I interviewed, space constraints are a huge challenge for Smith in maintaining his work over time, as Smith has limited room to store physical manifestations of the objects he creates. One strategy for this is to create modular works that collapse down into more manageable shapes.

For Smith, modularity is also a necessity as the CNC machine he uses to print out his digital objects can only cut out pieces of a particular size, meaning that larger works need to be assembled from these smaller components. Smith expressed several different instances of how he has adapted his creative process to account for these logistical difficulties, such as creating a sculpture that was the exact size and shape of the storage area in his hatchback car. Smith faces many specifically digital preservation issues as well, particularly with his VR work. VR technologies, according to Smith, have such a “high barrier for entry” as to discourage artists from adopting them and exploring their potential for art making. There is a limited community of practice of artists for these technologies, and even this limited community is fragmented, which does not bode well for the long term preservation of these works, which depend on complex software for both creation and access. For Smith, Paper-Thin is the start of a solution to this issue; he hopes that this online space can foster a community of artists using VR for art marking, serving to both raise the profile and importance of VR artists in the art world and to develop a critical mass of users for this technology so as to better address preservation issues as they arise.

These three profiles hopefully demonstrate the wide range of challenges that new media and installation artists face in the ongoing preservation of their artworks. Although I’m still working through the data and have yet to arrive at any well formulated conclusions, one thing that I have noticed again and again is the important role of the artists’ personal archives the preservation of their work. Artists use their archives to store documentation of performative or site-specific artworks, spare parts stripped from previous works, and supplemental documents from the process of a work’s creation or exhibition. Often, the artists don’t make any clear distinction between these materials and their body of stored artworks, all of this falling under the shared heading of the artist’s “archives.” For the preservation of new media artworks, this has some real implications. Perhaps institutions cannot just think about the ongoing maintenance of discrete artworks, but need to more seriously consider the preservation of artworks as more loosely defined groups of archival materials.

NOTES

[1] For one of the earliest articulations on the challenges of preserving new media art, see: Howard Besser, “Longevity of Electronic Art,” 2001, http://besser.tsoa.nyu.edu/howard/Papers/elect-art-longevity.html.

[2] DOCAM, “Presentation of the Model,” accessed September 13, 2015, http://www.docam.ca/en/documentation-model.html.

[3] Alain Depocas et al., Permanence through change: the variable media approach = L’Approche des médias variables : la permanence par le changement (New York; Montreal: Guggenheim Museum ; Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology, 2003).

[4] “Seeing Double: Emulation In Theory And Practice,” accessed September 13, 2015, http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/press-room/releases/press-release-archive/2004/643-march-3-seeing-double-emulation-in-theory-and-practice.